Introduction

The intersection of housing and health has garnered significant scholarly attention within public health discourse, particularly in the context of social determinants of health. Housing conditions exert a profound influence on health outcomes, with empirical evidence linking substandard housing to a myriad of health issues, including respiratory diseases, mental health disorders, and overall diminished well-being (Marmot, 2010). This article posits that housing can function as a vital conduit connecting individuals experiencing socio-economic inequalities to the National Health Service (NHS) and social care. By examining various partnerships and initiatives, this article highlights best practices and strategies for enhancing health equity through recognising housing associations as the ability to act as a human bridge, supporting and empowering people to access health pathways.

Health Inequalities in the UK

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines social determinants of health as the conditions in which individuals are born, grow, live, work, and age (WHO, 2019). Housing represents a fundamental social determinant that shapes health outcomes through pathways such as environmental exposures, socio-economic status, and access to healthcare services (Bambra et al., 2010).

Health inequalities in the United Kingdom are pronounced, with significant disparities in health outcomes observable across different socio-economic strata (Office for National Statistics, 2020). These inequalities are exacerbated by factors such as inadequate housing, which disproportionately impacts low-income families and marginalised communities (Baker et al., 2016). Due to the significant under supply of social housing only those in greatest need of social housing support receive it. The ripple effect has resulted in social housing customers living in the most deprived areas of the UK and being significantly overrepresented in all aspects of health inequalities.

The Role of Housing Providers

Housing providers occupy a unique position to identify and support vulnerable populations at risk of health issues due to suboptimal living conditions. By serving as a point of contact, housing services can facilitate access to health services, particularly for those encountering barriers such as language difficulties or lack of transportation (Baker et al., 2016).

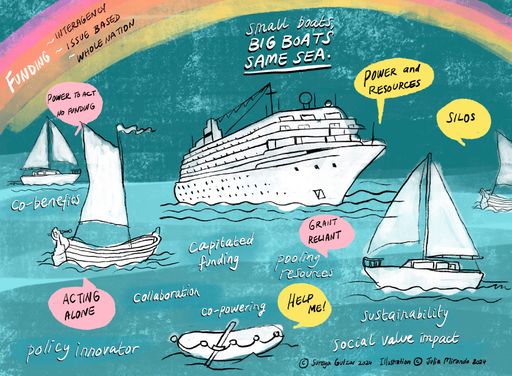

The housing as a human bridge to health access builds on a previous depiction of human bridges to demonstrate the ability of social housing landlords to scale the champion model to support and empower social housing residents to access preventative health pathways. (Sureya Gulzar 2021)

Case Studies

The Black Country Health and Housing Forum

The Black Country Health and Housing Forum exemplifies a collaborative approach to addressing health inequalities through housing interventions. The A.C.E (Asthma, Children, and the Environment) Programme, which recruits community champions from among tenants to support families grappling with asthma. This programme not only addresses housing conditions contributing to asthma but also facilitates access to health services, thereby enhancing health outcomes for affected families (Black Country Health and Housing Forum, 2021).

Worcester Health and Housing Partnership

The Worcester Health and Housing Partnership has concentrated on integrating health and housing data to identify vulnerable populations. By merging datasets, the partnership can effectively target interventions, ensuring that resources are allocated to areas most affected by poor housing conditions. This data-driven approach enhances the capacity of housing providers to address health disparities and inform policy-making (Worcester Health and Housing Partnership, 2020).

Manchester Health and Housing Partnership

The Manchester Health and Housing Partnership has implemented integrated services that facilitate a holistic approach to health and housing. By fostering collaboration between housing providers and health services, this partnership streamlines access to care for vulnerable populations, ensuring that individuals receive comprehensive support tailored to their needs (Manchester Health and Housing Partnership, 2021).

Initiatives aimed at enhancing housing quality can lead to improved health outcomes. For instance, addressing issues such as insulation and heating can significantly reduce the incidence of respiratory illnesses and other health problems associated with cold and damp homes (Marmot, 2010).

The Importance of Collaboration

The collaboration between housing and health sectors is essential for effectively addressing health inequalities. Integrated approaches that encompass both sectors can create synergies that enhance the efficacy of interventions and improve overall community health (Bambra et al., 2010).

Conclusion

This article elucidates the potential of housing as a conduit to health services for vulnerable populations suffering from socio-economic inequalities. The case studies presented demonstrate the efficacy of integrated approaches in addressing health disparities through housing interventions. As the discourse surrounding health and housing continues to evolve, it is imperative to maintain focus on these connections to foster well-being and equity for all. Future research should explore the long-term impacts of housing interventions on health outcomes and the potential for scaling successful initiatives across diverse regions.

References

Bambra, C., Gibson, M., Sowden, A., Woodhouse, A., & Wright, K. (2010). Tackling the wider social determinants of health and health inequalities: Evidence from systematic reviews. Journal of Public Health, 32(4), 1-12.

Baker, M., McCarthy, M., & Baird, J. (2016). The impact of housing on health: A systematic review. Public Health, 132, 1-12.

Black Country Health and Housing Forum. (2021). A.C.E Programme Report.

Manchester Health and Housing Partnership. (2021). Integrated Health and Housing Services: Annual Review.

Marmot, M. (2010). Fair Society, Healthy Lives: The Marmot Review.

Office for National Statistics. (2020). Health Inequalities in the UK.

WHO. (2019). Social Determinants of Health.

Worcester Health and Housing Partnership. (2020). Data Integration for Health Equity: A Case Study.